Isolated remains of

Homo erectus in Hathnora in the

Narmada Valley in central India indicate that India might have been inhabited since at least the

Middle Pleistocene era, somewhere between 500,000 and 200,000 years ago.

[29][30] Tools crafted by proto-humans that have been dated back two million years have been discovered in the northwestern part of the subcontinent.

[31][32] The ancient history of the region includes some of South Asia's oldest settlements

[33] and some of its major civilisations.

[34][35]

The

Mesolithic period in the Indian subcontinent was followed by the

Neolithic period, when more extensive settlement of the subcontinent occurred after the end of the last

Ice Age approximately 12,000 years ago. The first confirmed semipermanent settlements appeared 9,000 years ago in the

Bhimbetka rock shelters in modern

Madhya Pradesh, India.

Traces of a Neolithic culture have been alleged to be submerged in the

Gulf of Khambat in India,

radiocarbon dated to 7500 BCE.

[48] Neolithic agricultural cultures sprang up in the Indus Valley region around 5000 BCE, in the lower Gangetic valley around 3000 BCE, and in later South India, spreading southwards and also northwards into

Malwaaround 1800 BCE. The first urban civilisation of the region began with the

Indus Valley Civilisation.

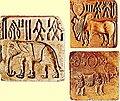

Indus Valley Civilisation

- Indus Valley Civilisation

|

|

|

-

Dholavira, one of the largest cities of Indus Valley Civilisation.

|

The civilisation was primarily located in modern-day India (

Gujarat,

Haryana,

Punjab and

Rajasthan provinces) and Pakistan (

Sindh,

Punjab, and

Balochistan provinces). Historically part of

Ancient India, it is one of the world's earliest urban civilisations, along with Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt.

[59] Inhabitants of the ancient Indus river valley, the Harappans, developed new techniques in metallurgy and handicraft (carneol products, seal carving), and produced copper, bronze, lead, and tin.

The Mature Indus civilisation flourished from about 2600 to 1900 BCE, marking the beginning of urban civilisation on the subcontinent. The civilisation included urban centres such as

Dholavira,

Kalibangan,

Ropar,

Rakhigarhi, and

Lothalin modern-day India, as well as

Harappa,

Ganeriwala, and

Mohenjo-daro in modern-day Pakistan. The civilisation is noted for its cities built of brick, roadside drainage system, and multistoreyed houses and is thought to have had some kind of municipal organisation.

[60]

During the

late period of this civilisation, signs of a

gradual decline began to emerge, and by around 1700 BCE, most of the cities were abandoned. However, the Indus Valley Civilisation did not disappear suddenly, and some elements of the Indus Civilisation may have survived, especially in the smaller villages and isolated farms. The Indian

Copper Hoard Culture is attributed to this time, associated in the Doab region with the

Ochre Coloured Pottery.

Vedic period (c. 1750 BCE–600 BCE)

| [show]Spread of IE-languages |

|---|

| [show]Indo-Aryan migration |

|---|

The

Vedic period is named after the

Indo-Aryan culture of north-west India, although other parts of India had a distinct cultural identity during this period. The Vedic culture is described in the texts of

Vedas, still sacred to Hindus, which were orally composed in

Vedic Sanskrit. The Vedas are some of the oldest extant texts in India. The Vedic period, lasting from about 1750 to 500 BCE,

[62][63] contributed the foundations of several cultural aspects of the Indian subcontinent. In terms of culture, many regions of the subcontinent transitioned from the

Chalcolithic to the

Iron Age in this period.

[64]

Vedic society

A steel engraving from the 1850s, which depicts the creative activities of

Prajapati, a Vedic deity who presides over procreation and protection of life.

Historians have analysed the Vedas to posit a Vedic culture in the

Punjab region and the upper

Gangetic Plain.

[64] Most historians also consider this period to have encompassed several waves of

Indo-Aryan migration into the subcontinent from the north-west.

[65][66] The

peepal tree and cow were sanctified by the time of the

Atharva Veda.

[67] Many of the concepts of Indian philosophy espoused later like Dharma, Karma etc. trace their root to the Vedas.

[68]

Early Vedic society is described in the

Rigveda, the oldest Vedic text, believed to have been compiled during 2nd millennium BCE,

[69][70] in the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent.

[71] At this time, Aryan society consisted of largely tribal and pastoral groups, distinct from the Harappan urbanisation which had been abandoned.

[72]The early Indo-Aryan presence probably corresponds, in part, to the

Ochre Coloured Pottery culture in archaeological contexts.

[74]

At the end of the Rigvedic period, the Aryan society began to expand from the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent, into the western

Ganges plain. It became increasingly agricultural and was socially organised around the hierarchy of the four

varnas, or social classes. This social structure was characterised both by syncretising with the native cultures of northern India, but also eventually by the excluding of indigenous peoples by labelling their occupations impure.

[76] During this period, many of the previous small tribal units and chiefdoms began to coalesce into

monarchical, state-level polities.

Sanskritisation

Since Vedic times,

[78][note 2] "people from many strata of society throughout the subcontinent tended to adapt their religious and social life to Brahmanic norms", a process sometimes called

Sanskritisation.

[78] It is reflected in the tendency to identify local deities with the gods of the Sanskrit texts.

[78]

The

Kuru kingdom was the first state-level society of the Vedic period, corresponding to the beginning of the Iron Age in northwestern India, around 1200 – 800 BCE,

[79] as well as with the composition of the

Atharvaveda (the first Indian text to mention iron, as

śyāma ayas, literally "black metal").

[80] The Kuru state organised the Vedic hymns into collections, and developed the orthodox

srauta ritual to uphold the social

ORDER

.

[81] When the Kuru kingdom declined, the centre of Vedic culture shifted to their eastern neighbours, the

Panchala kingdom.

[81] The archaeological

Painted Grey Ware culture, which flourished in the

Haryana and western

Uttar Pradesh regions of northern India from about 1100 to 600 BCE, is believed to correspond to the

Kuru and Panchala kingdoms.

[81]

During the Late Vedic Period, the kingdom of

Videha emerged as a new centre of Vedic culture, situated even farther to the East (in what is today Nepal and

Bihar state in India).

[74] The later part of this period corresponds with a consolidation of increasingly large states and kingdoms, called

mahajanapadas, all across Northern India.

Sanskrit Epics

In addition to the Vedas, the principal texts of Hinduism, the core themes of the Sanskrit epics

Ramayana and

Mahabharata are said to have their ultimate origins during this period.

[83] The

Mahabharata remains, today, the longest single poem in the world.

[84] Historians formerly postulated an "epic age" as the milieu of these two epic poems, but now recognise that the texts (which are both familiar with each other) went through multiple stages of development over centuries. For instance, the

Mahabharata may have been based on a small-scale conflict (possibly about 1000 BCE) which was eventually "transformed into a gigantic epic war by bards and poets". There is no conclusive proof from archaeology as to whether the specific events of the Mahabharat have any historical basis. The existing texts of these epics are believed to belong to the post-Vedic age, between c. 400 BCE and 400 CE.

[86] Some even attempted to date the events using methods of

archaeoastronomy which have produced, depending on which passages are chosen and how they are interpreted, estimated dates ranging up to mid 2nd millennium BCE.

[87][88]

"Second urbanisation" (c. 600 BCE–200 BCE)

During the time between 800 and 200 BCE the

Shramana-movement formed, from which originated

Jainism and

Buddhism. In the same period the first

Upanishads were written. After 500 BCE, the so-called "Second urbanisation" started, with new urban settlements arising at the Ganges plain, especially the Central Ganges plain. The Central Ganges Plain, where

Magadha gained prominence, forming the base of the

Mauryan Empire, was a distinct cultural area, with new states arising after 500 BC

[web 1] during the so-called "Second urbanisation".

[note 3] It was influenced by the Vedic culture, but differed markedly from the Kuru-Panchala region. It "was the area of the earliest known cultivation of rice in South Asia and by 1800 BC was the location of an advanced neolithic population associated with the sites of Chirand and Chechar". In this region the

Shramanic movements flourished, and Jainism and Buddhism originated.

Mahajanapadas

The

Mahajanapadas were the sixteen most powerful kingdoms and republics of the era, located mainly across the fertile

Indo-Gangetic plains, there were a number of smaller kingdoms stretching the length and breadth of

Ancient India.

In the later Vedic Age, a number of small kingdoms or city states had covered the subcontinent, many mentioned in Vedic, early Buddhist and Jaina literature as far back as 500 BCE. sixteen monarchies and "republics" known as the Mahajanapadas—

Kashi,

Kosala,

Anga,

Magadha,

Vajji (or Vriji),

Malla,

Chedi,

Vatsa (or Vamsa),

Kuru,

Panchala,

Matsya (or Machcha),

Shurasena,

Assaka,

Avanti,

Gandhara, and

Kamboja—stretched across the

Indo-Gangetic Plain from modern-day Afghanistan to

Bengal and

Maharashtra. This period saw the second major rise of urbanism in India after the

Indus Valley Civilisation.

Many smaller clans mentioned within early literature seem to have been present across the rest of the subcontinent. Some of these kings were hereditary; other states elected their rulers. Early "republics" such as the Vajji (or Vriji) confederation centred in the city of

Vaishali, existed as early as the 6th century BCE and persisted in some areas until the 4th century CE. The educated speech at that time was

Sanskrit, while the languages of the general population of northern India are referred to as

Prakrits. Many of the sixteen kingdoms had coalesced to four major ones by 500/400 BCE, by the time of

Gautama Buddha. These four were Vatsa, Avanti, Kosala, and Magadha. The Life of Gautam Budhha was mainly associated with these four kingdoms.

Upanishads and Shramana movements

The 7th and 6th centuries BC witnessed the composition of the earliest Upanishads.

[95][96] Upanishads form the theoretical basis of classical Hinduism and are known as

Vedanta (conclusion of the

Vedas).

[97] The older Upanishads launched attacks of increasing intensity on the ritual. Anyone who worships a divinity other than the Self is called a domestic animal of the gods in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad. The Mundaka launches the most scathing attack on the ritual by comparing those who value sacrifice with an unsafe boat that is endlessly overtaken by old age and death.

[98]

Increasing urbanisation of India in 7th and 6th centuries BCE led to the rise of new ascetic or shramana movements which challenged the orthodoxy of rituals.

[95] Mahavira (c. 549–477 BC), proponent of

Jainism, and

Gautama Buddha (c. 563-483), founder of Buddhism were the most prominent icons of this movement. Shramana gave rise to the concept of the cycle of birth and death, the concept of

samsara, and the concept of liberation.

[99] Buddha found a

Middle Way that ameliorated the extreme

asceticism found in the

Sramana religions.

[100]

Around the same time,

Mahavira (the 24th

Tirthankara in Jainism) propagated a theology that was to later become Jainism.

[101] However, Jain orthodoxy believes the teachings of the Tirthankaras predates all known time and scholars believe

Parshvanath, accorded status as the 23rd Tirthankara, was a historical figure. Rishabhdeo was the 1st Tirthankara. The Vedas are believed to have documented a few Tirthankaras and an ascetic

ORDER

similar to the shramana movement.

[102]

Magadha dynasties

The Magadha state c. 600 BCE, before it expanded from its capital

Rajagriha.

Magadha (

Sanskrit:

मगध) formed one of the sixteen

Mahā-Janapadas (

Sanskrit: "Great Countries") or

kingdoms in ancient India. The core of the kingdom was the area of

Bihar south of the

Ganges; its first capital was

Rajagriha (modern Rajgir) then

Pataliputra (modern

Patna). Magadha expanded to include most of Bihar and

Bengal with the conquest of

Licchavi and

Anga respectively,

[103] followed by much of eastern Uttar Pradesh and Orissa. The ancient kingdom of Magadha is heavily mentioned in

Jain and Buddhist texts. It is also mentioned in the

Ramayana,

Mahabharata,

Puranas.

[104] The earliest reference to the Magadha people occurs in the

Atharva-Veda where they are found listed along with the

Angas,

Gandharis, and Mujavats. Magadha played an important role in the development of

Jainism and Buddhism, and two of India's greatest empires, the

Maurya Empire and

Gupta Empire, originated from Magadha. These empires saw advancements in ancient India's science, mathematics,

astronomy, religion, and philosophy and were considered the Indian "

Golden Age". The Magadha kingdom included republican communities such as the community of Rajakumara. Villages had their own assemblies under their local chiefs called Gramakas. Their administrations were divided into executive, judicial, and military functions.

The Haryanka dynasty was overthrown by the

Shishunaga dynasty. The last Shishunaga ruler, Kalasoka, was assassinated by

Mahapadma Nanda in 345 BCE, the first of the so-called Nine Nandas, Mahapadma and his eight sons.

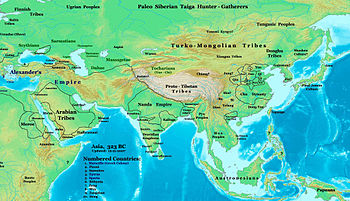

Persian and Greek conquests in Northwestern South Asia

In 530 BC

Cyrus the Great, King of the Persian

Achaemenid Empire crossed the Hindu-Kush mountains to seek tribute from the tribes of Kamboja, Gandhara and the trans-India region (modern Afghanistan and Pakistan).

[106] By 520 BC, during the reign of Darius I of Persia, much of the northwestern subcontinent (present-day eastern Afghanistan and Pakistan) came under the rule of the Persian Achaemenid Empire, as part of the far easternmost territories. The area remained under Persian control for two centuries.

[107] During this time India supplied mercenaries to the Persian army then fighting in Greece.

[106]

Under Persian rule the famous city of

Takshashila became a centre where both Vedic and Iranian learning were mingled.

[108] Persian ascendency in Northwestern South Asia ended with

Alexander the Great's conquest of Persia in 327 BC.

[109]

By 326 BC, Alexander the Great had conquered Asia Minor and the Achaemenid Empire and had reached the northwest frontiers of the Indian subcontinent. There he defeated

King Porus in the

Battle of the Hydaspes (near modern-day

Jhelum, Pakistan) and conquered much of the

Punjab.

[110]Alexander's march east put him in confrontation with the

Nanda Empire of

Magadha and the

Gangaridai of

Bengal. His army, exhausted and frightened by the prospect of facing larger Indian armies at the Ganges River, mutinied at the Hyphasis (modern

Beas River) and refused to march further East. Alexander, after the meeting with his officer,

Coenus, and learning about the might of

Nanda Empire, was convinced that it was better to return.

The Persian and Greek invasions had repercussions in the Northwestern regions of the Indian subcontinent. The region of Gandhara, or present-day eastern Afghanistan and northwest Pakistan, became a melting pot of Indian, Persian, Central Asian, and Greek cultures and gave rise to a

HYBRID

culture,

Greco-Buddhism, which lasted until the 5th century AD and influenced the artistic development of

Mahayana Buddhism.

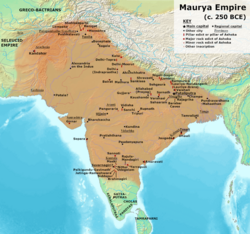

Maurya Empire

The Maurya Empire (322–185 BCE) was the first empire to unify India into one state, and was the largest on the Indian subcontinent. At its greatest extent, the Mauryan Empire stretched to the north up to the natural boundaries of the

Himalayas and to the east into what is now

Assam. To the west, it reached beyond modern Pakistan, to the

Hindu Kush mountains in what is now Afghanistan. The empire was established by

Chandragupta Maurya assisted by Chanakya (

Kautilya) in

Magadha (in modern

Bihar) when he overthrew the

Nanda Dynasty.

[111] Chandragupta's son

Bindusara succeeded to the throne around 297 BC. By the time he died in c. 272 BC, a large part of the subcontinent was under Mauryan suzerainty. However, the region of

Kalinga (around modern day

Odisha) remained outside Mauryan control, perhaps interfering with their trade with the south.

Bindusara was succeeded by

Ashoka, whose reign lasted for around thirty seven years until his death in about 232 BCE. His campaign against the Kalingans in about 260 BCE, though successful, lead to immense loss of life and misery. This filled Ashoka with remorse and lead him to shun violence, and subsequently to embrace Buddhism. The empire began to decline after his death and the last Mauryan ruler,

Brihadratha, was assassinated by

Pushyamitra Shunga to establish the

Shunga Empire.

The

Arthashastra and the

Edicts of Ashoka are the primary written records of the Mauryan times. Archaeologically, this period falls into the era of

Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW). The Mauryan Empire was based on a modern and efficient economy and society. However, the

SALE

of merchandise was closely regulated by the government.

[114] Although there was no banking in the Mauryan society, usury was customary. A significant amount of written records on slavery are found, suggesting a prevalence thereof. During this period, a high quality steel called

Wootz steel was developed in south India and was later exported to China and Arabia.

[13]

Sangam Period

The Sangam literature

DEALS

with the history, politics, wars and culture of the Tamil people of this period.

[117] The scholars of the Sangam period rose from among the common people who sought the patronage of the Tamil Kings, but who mainly wrote about the common people and their concerns.

[118] Unlike Sanskrit writers who were mostly Brahmins, Sangam writers came from diverse classes and social backgrounds and were mostly non-Brahmins. They belonged to different faiths and professions like farmers, artisans, merchants, monks, priests and even princes and quite few of them were even

WOMEN

.

[118]

Classical period (c. 200 BCE–1200 CE)

The time between 200 BCE and ca. 1100 CE is the "Classical Age" of India. It can be divided in various sub-periods, depending on the chosen periodisation. Classical period begins after the decline of the

Maurya Empire, and the corresponding rise of the

Satavahana dynasty, beginning with

Simuka, from 230 BCE. The

Gupta Empire (4th–6th century) is regarded as the "Golden Age" of Hinduism, although a host of kingdoms ruled over India in these centuries. Also, the

Sangam literature flourished from the 3rd century BCE to the 3rd century CE in southern India.

[12] During this period, India is estimated to have had the largest economy in the world; controlling between one third and one fourth of the world's wealth.

[119][120]

Early Classical period (c. 200 BCE–320 CE)

Satavahana Dynasty

Reliefs depicting life of Buddha, Satavhana Dynasty, 3rd century BC.

The

Śātavāhana Empire was a royal Indian dynasty based from

Amaravati in

Andhra Pradesh as well as

Junnar (

Pune) and Prathisthan (

Paithan) in

Maharashtra. The territory of the empire covered much of India from 230 BCE onward. Sātavāhanas started out as feudatories to the

Mauryan dynasty, but declared independence with its decline. They are known for their patronage of Hinduism and Buddhism which resulted in Buddhist monuments from

Ellora (a

UNESCO World Heritage Site) to

Amaravati. The Sātavāhanas were one of the first Indian states to issue coins struck with their rulers embossed. They formed a cultural bridge and played a vital role in trade as well as the transfer of ideas and culture to and from the

Indo-Gangetic Plain to the southern tip of India. They had to compete with the

Shunga Empire and then the

Kanva dynasty of

Magadha to establish their rule. Later, they played a crucial role to protect a huge part of India against foreign invaders like the

Sakas,

Yavanas and

Pahlavas. In particular their struggles with the

Western Kshatrapas went on for a long time. The notable rulers of the Satavahana Dynasty

Gautamiputra Satakarni and

Sri Yajna Sātakarni were able to defeat the foreign invaders like the

Western Kshatrapas and to stop their expansion. In the 3rd century CE the empire was split into smaller states.

Shunga Empire

The Shunga Empire was an ancient Indian dynasty from

Magadha that controlled vast areas of the Indian subcontinent from around 187 to 78 BCE. The dynasty was established by

Pushyamitra Shunga, after the fall of the

Maurya Empire. Its capital was

Pataliputra, but later emperors such as

Bhagabhadra also held court at

Besnagar, modern

Vidisha in Eastern

Malwa.

[121] Pushyamitra Shunga ruled for 36 years and was succeeded by his son

Agnimitra. There were ten Shunga rulers. The empire is noted for its numerous wars with both foreign and indigenous powers. They fought battles with the

Kalingas,

Satavahanas, the

Indo-Greeks, and possibly the

Panchalas and

Mathuras. Art, education, philosophy, and other forms of learning flowered during this period including small terracotta images, larger stone sculptures, and architectural monuments such as the Stupa at

Bharhut, and the renowned Great Stupa at

Sanchi. The Shunga rulers helped to establish the tradition of royal sponsorship of learning and art. The script used by the empire was a variant of

Brahmi and was used to write the

Sanskrit language. The Shunga Empire played an imperative role in patronising

Indian culture at a time when some of the most important developments in Hindu thought were taking place. This helped the empire flourish and gain power.

Mahameghavahana Empire

The Hathigumpha inscription of Kharavela

Kaḷingan military might was reinstated by Khārabēḷa: under Khārabēḷa's generalship, the Kaḷinga state had a formidable maritime reach with trade routes linking it to the then-Simhala (Sri Lanka), Burma (Myanmar), Siam (Thailand), Vietnam, Kamboja (Cambodia), Malaysia, Borneo, Bali, Samudra (Sumatra) and Jabadwipa (Java). Khārabēḷa led many successful campaigns against the states of Magadha, Anga, Satavahanas till the southern most regions of Pandyan Empire (modern Tamil Nadu).

The empire was a maritime power with trading routes linking it to Sri Lanka, Burma, Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia,

Borneo,

Bali,

Sumatra, and

Java. Colonists from Kalinga settled in Sri Lanka, Burma, as well as the Maldives and

Maritime Southeast Asia.

Northwestern kingdoms and hybrid cultures

The Northwestern kingdoms and

HYBRID

cultures of the Indian subcontinent included the

Indo-Greeks, the

Indo-Scythians, the

Indo-Parthians, and the

Indo-Sassinids.

- Indo-Greek Kingdom: The Indo-Greek Menander I (reigned 155–130 BCE) drove the Greco-Bactrians out of Gandhara and beyond the Hindu Kush, becoming a king shortly after his victory. His territories covered Panjshir and Kapisa in modern Afghanistan and extended to the Punjab region, with many tributaries to the south and east. The capital Sagala (modern Sialkot) prospered greatly under Menander's rule.[123] The classical Buddhist text Milinda Pañha praises Menander, saying there was "none equal to Milinda in all India".[124] Lasting for almost two centuries, the kingdom was ruled by a succession of more than 30 Indo-Greek kings, who were often in conflict with each other.

- Indo-Scythian Kingdom: The Indo-Scythians were descended from the Sakas (Scythians) who migrated from southern Siberia to Pakistan and Arachosia to India from the middle of the 2nd century BCE to the 1st century BCE. They displaced the Indo-Greeks and ruled a kingdom that stretched from Gandhara to Mathura. The power of the Saka rulers started to decline in the 2nd century CE after the Scythians were defeated by the south Indian Emperor Gautamiputra Satakarni of the Satavahana dynasty.[125]Later the Saka kingdom was completely destroyed by Chandragupta II of the Gupta Empire from eastern India in the 4th century.[127]

- Indo-Parthian Kingdom: The Indo-Parthian Kingdom was ruled by the Gondopharid dynasty, named after its eponymous first ruler Gondophares. They ruled parts of present-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northwestern India,[128] during or slightly before the 1st century AD. For most of their history, the leading Gondopharid kings held Taxila(in the present Punjab province of Pakistan) as their residence and ruled from there, but during their last few years of existence the capital shifted between Kabul andPeshawar. These kings have traditionally been referred to as Indo-Parthians, as their coinage was often inspired by the Arsacid dynasty, but they probably belonged to a wider groups of Iranian tribes who lived east of Parthia proper, and there is no evidence that all the kings who assumed the title Gondophares, which means "Holder of Glory", were even related.

- Indo-Sassanid Kingdom: The Sassanid empire of Persia, who was contemporaneous with the Gupta Empire, expanded into the region of present-day Balochistan in Pakistan, where the mingling of Indian culture and the culture of Iran gave birth to aHYBRID

culture under the Indo-Sassanids.

culture under the Indo-Sassanids.

Trade and Travels to India

Silk Road and

Spice trade, ancient trade routes that linked India with the

Old World; carried goods and ideas between the ancient civilisations of the Old World and India. The land routes are red, and the water routes are blue.

The

spice trade in

Kerala attracted traders from all over the Old World to India. Early writings and Stone Age carvings of

neolithic age obtained indicates that India's Southwest coastal port

Muziris, in Kerala, had established itself as a major spice trade centre from as early as 3,000 BCE, according to

Sumerian records. Kerala was referred to as the land of spices or as the "Spice Garden of India". It was the place traders and exporters wanted to reach, including

Christopher Colombus,

Vasco da Gama, and others.

[129]

Buddhism entered China through the

Silk Road transmission of Buddhism in the 1st or 2nd century CE. The interaction of cultures resulted in several Chinese travellers and monks to enter India. Most notable were

Faxian,

Yijing,

Song Yun and

Xuanzang. These travellers wrote detailed accounts of the Indian Subcontinent, which includes the political and social aspects of the region.

[130]

Hindu and Buddhist religious establishments of Southeast Asia came to be associated with the economic activity and commerce as patrons entrust large funds which would later be used to benefit local economy by estate management, craftsmanship,

PROMOTION

of trading activities. Buddhism in particular, travelled alongside the maritime trade, promoting coinage, art and literacy.

[131] Indian merchants involved in spice trade took

Indian cuisine to Southeast Asia, where spice mixtures and

curries became popular with the native inhabitants.

[132]

Strabo, whose

Geography is the main surviving source of the story, was sceptical about its truth. Modern scholarship tends to consider it relatively credible. During the 2nd century BC Greek and Indian ships met to trade at

Arabian ports such as

Aden (called

Eudaemon by the Greeks).

[135] Another Greek navigator,

Hippalus, is sometimes credited with discovering the monsoon wind route to India. He is sometimes conjectured to have been part of Eudoxus's expeditions.

[136]

Kushan Empire

Kushan territories (full line) and maximum extent of Kushan dominions under Kanishka (dotted line), according to the Rabatak inscription.

Emperor Kanishka was a great patron of

Buddhism; however, as Kushans expanded southward, the deities

[141] of their later coinage came to reflect its new

Hindu majority.

[142]

They played an important role in the establishment of Buddhism in India and its spread to Central Asia and China.

He played the part of a second Ashoka in the history of Buddhism.

[143]

The empire linked the Indian Ocean maritime trade with the commerce of the

Silk Road through the Indus valley, encouraging long-distance trade, particularly between China and

Rome. The Kushans brought new trends to the budding and blossoming

Gandhara Art, which reached its peak during Kushan Rule.

H.G. Rowlinson commented:

The Kushan period is a fitting prelude to the Age of the Guptas.

[144]

By the 3rd century, their empire in India was disintegrating and their last known great emperor was

Vasudeva I.

[145][146]

Classical period (c. 320-650 CE)

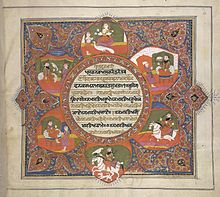

Gupta Empire - Golden Age

Classical India refers to the period when much of the Indian subcontinent was reunited under the Gupta Empire (c. 320–550 CE).

[147][148] This period has been called the Golden Age of India

[149] and was marked by extensive achievements in

science, technology,

engineering,

art,

dialectic,

literature,

logic,

mathematics,

astronomy,

religion, and

philosophythat crystallised the elements of what is generally known as

Hindu culture.

[150] The

Hindu-Arabic numerals, a

positional numeral system, originated in India and was later transmitted to the West through the Arabs. Early Hindu numerals had only nine symbols, until 600 to 800 CE, when a symbol for zero was developed for the numeral system.

[151]The peace and prosperity created under leadership of Guptas enabled the pursuit of scientific and artistic endeavours in India.

[152]

The high points of this cultural creativity are magnificent architecture, sculpture, and painting.

[153] The Gupta period produced scholars such as

Kalidasa,

Aryabhata,

Varahamihira,

Vishnu Sharma, and

Vatsyayana who made great advancements in many academic fields.

[154] The Gupta period marked a watershed of Indian culture: the Guptas performed Vedic sacrifices to legitimise their rule, but they also patronised Buddhism, which continued to provide an alternative to Brahmanical orthodoxy. The military exploits of the first three rulers –

Chandragupta I,

Samudragupta, and

Chandragupta II - brought much of India under their leadership.

[155] Science and political administration reached new heights during the Gupta era. Strong trade ties also made the region an important cultural centre and established it as a base that would influence nearby kingdoms and regions in Burma, Sri Lanka,

Maritime Southeast Asia, and

Indochina.

Historian Dr. Barnett remarked:

However, some historians like

D.N.Jha disagree:

The much published Hindu renaissance was, in reality, not a renaissance, much less a Hindu one.

[157]

The latter Guptas successfully resisted the northwestern kingdoms until the arrival of the

Hunas, who established themselves in Afghanistan by the first half of the 5th century, with their capital at

Bamiyan.

[158] However, much of the

Deccan and southern India were largely unaffected by these events in the north.

[159][160]

Vakataka Dynasty

The Vākāṭaka Empire (

Marathi:

वाकाटक) was a royal Indian

dynasty that originated from the

Deccan in the mid-third century CE. Their state is believed to have extended from the southern edges of

Malwa and

Gujarat in the north to the

Tungabhadra River in the south as well as from the

Arabian Sea in the western to the edges of

Chhattisgarh in the east. They were the most important successors of the

Satavahanas in the

Deccan and contemporaneous with the

Guptas in northern India.

The Vakatakas are noted for having been patrons of the arts, architecture and literature. They led public works and their monuments are a visible legacy. The rock-cut Buddhist viharas and chaityas of

Ajanta Caves (a

UNESCO World Heritage Site) were built under the patronage of Vakataka emperor,

Harishena.

[161][162]

Kamarupa Kingdom

Davaka was later absorbed by Kamarupa, which grew into a large kingdom that spanned from Karatoya river to near present

Sadiya and covered the entire Brahmaputra valley,

North Bengal, parts of

Bangladesh and, at times

Purnea and parts of

West Bengal.

[165]

In the reign of the Varman king,

Bhaskar Varman (c. 600–650 AD), the Chinese traveller

Xuanzang visited the

region and recorded his travels. Later, after weakening and disintegration (after the Kamarupa-Palas), the Kamarupa tradition was somewhat extended till c. 1255 AD by the Lunar I (c. 1120–1185 AD) and Lunar II (c. 1155–1255 AD) dynasties.

[167]

Pallava Dynasty

The

Pallavas, during the 4th to 9th centuries were, alongside the

Guptas of the

North, great patronisers of Sanskrit development in the

South of the

Indian subcontinent. The Pallava reign saw the first Sankrit inscriptions in a script called

Grantha.

[168] Early Pallavas had different connexions to

Southeast Asian countries. The Pallavas used Dravidian architecture to build some very important Hindu temples and academies in

Mamallapuram,

Kanchipuram and other places; their rule saw the rise of great poets. The practice of dedicating temples to different deities came into vogue followed by fine artistic

temple architecture and sculpture style of

Vastu Shastra.

[169]

Kadamba Dynasty

Kadamba (345 – 525 CE) was an ancient royal dynasty of

Karnataka, India that ruled northern Karnataka and the Konkan from

Banavasiin present-day

Uttara Kannada district. At the peak of their power under King Kakushtavarma, the Kadambas of Banavasi ruled large parts of modern Karnataka state.

The dynasty was founded by

Mayurasharma in 345 CE which at later times showed the potential of developing into imperial proportions, an indication to which is provided by the titles and epithets assumed by its rulers. King Mayurasharma defeated the armies of

Pallavas of Kanchi possibly with help of some native tribes. The Kadamba fame reached its peak during the rule of

Kakusthavarma, a notable ruler with whom even the kings of

Gupta Dynasty of northern India cultivated marital alliances. The Kadambas were contemporaries of the

Western Ganga Dynasty and together they formed the earliest native kingdoms to rule the land with absolute autonomy. The dynasty later continued to rule as a feudatory of larger Kannada empires, the

Chalukya and the

Rashtrakuta empires, for over five hundred years during which time they branched into minor dynasties known as the

Kadambas of Goa,

Kadambas of Halasi and

Kadambas of Hangal.

The White Huns

The Hephthalites (or Ephthalites), also known as the White Huns, were a nomadic confederation in Central Asia during the late antiquity period. The

White Huns established themselves in modern-day Afghanistan by the first half of the 5th century. Led by the Hun military leader

Toramana, they overran the northern region of Pakistan and North India. Toramana's son

Mihirakula, a

Saivite Hindu, moved up to near

Pataliputra to the east and

Gwalior to the central India.

Hiuen Tsiang narrates Mihirakula's merciless persecution of Buddhists and destruction of monasteries, though the description is disputed as far as the authenticity is concerned.

[171] The Huns were defeated by the Indian kings

Yasodharman of Malwa and Narasimhagupta in the 6th century. Some of them were driven out of India and others were assimilated in the Indian society.

[172]

Empire of Harsha

After the downfall of the prior

Gupta Empire in the middle of the 6th century,

North India reverted to small republics and small monarchical states ruled by Gupta rulers. Harsha was a

CONVERT

to Buddhism.

[173] He united the small republics from Punjab to central India, and their representatives crowned Harsha king at an assembly in April 606 giving him the title of Maharaja when he was merely 16 years old. Harsha belonged to Kanojia.

[174] He brought all of northern India under his control.

[175] The peace and prosperity that prevailed made his court a centre of cosmopolitanism, attracting scholars, artists and religious visitors from far and wide.

[175] The Chinese traveller Xuan Zang visited the court of Harsha and wrote a very favourable account of him, praising his justice and generosity.

[175]

Late Classical period (c. 650–1200 CE)

From the fifth century to the thirteenth,

Śrauta sacrifices declined, and initiatory traditions of

Buddhism,

Jainism or more commonly

Shaivism,

Vaishnavism and

Shaktismexpanded in royal courts.

[3] This period produced some of India's finest art, considered the epitome of classical development, and the development of the main spiritual and philosophical systems which continued to be in Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism.

North-Western Indian Buddhism weakened in the 6th century after the

White Hun invasion, who followed their own religions at the beginning such as

Tengri, but later

Indian religions.

Muhammad bin Qasim's invasion of

Sindh (modern Pakistan) in 711 CE witnessed further decline of Buddhism. The

Chach Nama records many instances of conversion of stupas to mosques such as at

Nerun.

[178]

In the 7th century CE,

Kumārila Bhaṭṭa formulated his school of

Mimamsa philosophy and defended the position on Vedic rituals against Buddhist attacks. Scholars note Bhaṭṭa's contribution to the

decline of Buddhism in India.

[179] His dialectical success against the Buddhists is confirmed by Buddhist historian

Tathagata, who reports that Kumārila defeated disciples of Buddhapalkita, Bhavya, Dharmadasa, Dignaga and others.

[180]

In the 8th century,

Adi Shankara travelled across the Indian subcontinent to propagate and spread the doctrine of

Advaita Vedanta, which he consolidated; and is credited with unifying the main characteristics of the current thoughts in Hinduism.

[181][182][183] He was a critic of both Buddhism and Minamsa school of Hinduism;

[184][185][186][187]and founded

mathas (monasteries), in the four corners of the Indian subcontinent for the spread and development of Advaita Vedanta.

[188]

Ronald Inden writes that by the 8th century CE symbols of Hindu gods "replaced the Buddha at the imperial centre and pinnacle of the cosmo-political system, the image or symbol of the Hindu god comes to be housed in a monumental temple and given increasingly elaborate imperial-style puja worship".

[189] Although Buddhism did not disappear from India for several centuries after the eighth, royal proclivities for the cults of Vishnu and Shiva weakened Buddhism's position within the sociopolitical context and helped make possible its decline.

[190]

Emperor Harsha of

Kannauj succeeded in reuniting northern India during his reign in the 7th century, after the collapse of the Gupta dynasty. His empire collapsed after his death.

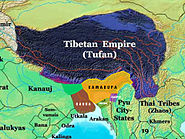

From the 8th to the 10th century, three dynasties contested for control of northern India: the

Gurjara Pratiharas of Malwa, the

Palas of Bengal, and the

Rashtrakutas of the Deccan. The

Sena dynasty would later assume control of the Pala Empire, and the Gurjara Pratiharas fragmented into various states. These were the first of the

Rajputstates. The first recorded

Rajput kingdoms emerged in

Rajasthan in the 6th century, and small Rajput dynasties later ruled much of northern India. One

Gurjar[191][192]Rajput of the

Chauhan clan,

Prithvi Raj Chauhan, was known for bloody conflicts against the advancing Turkic sultanates.

Chalukya Empire

The

Chalukya Empire (

Kannada:

ಚಾಲುಕ್ಯರು [tʃaːɭukjə]) was an Indian royal dynasty that ruled large parts of

southern and

central India between the 6th and the 12th centuries. During this period, they ruled as three related yet individual dynasties. The earliest dynasty, known as the "Badami Chalukyas", ruled from Vatapi (modern

Badami) from the middle of the 6th century. The Badami Chalukyas began to assert their independence at the decline of the

Kadamba kingdom of

Banavasi and rapidly rose to prominence during the reign of

Pulakeshin II. The rule of the Chalukyas marks an important milestone in the history of

South India and a golden age in the history of

Karnataka. The political atmosphere in South India shifted from smaller kingdoms to large empires with the ascendancy of Badami Chalukyas. A Southern India-based kingdom took control and consolidated the entire region between the

Kaveri and the

Narmada rivers. The rise of this empire saw the birth of efficient administration, overseas trade and commerce and the development of new style of architecture called "Chalukyan architecture". The

Chalukya dynasty ruled parts of southern and central India from Badami in Karnataka between 550 and 750, and then again from

Kalyani between 970 and 1190.

The

Solanki dynasty of Gujarat were a branch of the Chalukyas. Their capital at Anhilwara (modern

Patan, Gujarat) was one of the largest cities in Classical India, with population estimated at 100,000 in 1000 CE.

Rashtrakuta Empire

Founded by

Dantidurga around 753, the Rashtrakuta Empire ruled from its capital at

Manyakheta for almost two centuries.

[198]At its peak, the Rashtrakutas ruled from the Ganges River and Yamuna River doab in the north to Cape Comorin in the south, a fruitful time of political expansion, architectural achievements and famous literary contributions.

[199][200]

The early rulers of this dynasty were Hindu, but the later rulers were strongly influenced by Jainism.

Govinda III and

Amoghavarsha were the most famous of the long line of able administrators produced by the dynasty. Amoghavarsha, who ruled for 64 years, was also an author and wrote

Kavirajamarga, the earliest known Kannada work on poetics.

[198] Architecture reached a milestone in the Dravidian style, the finest example of which is seen in the Kailasanath Temple at Ellora. Other important contributions are the sculptures of Elephanta Caves in modern Maharashtra as well as the Kashivishvanatha temple and the Jain Narayana temple at Pattadakal in modern Karnataka, all of which are UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

The Arab traveller Suleiman described the Rashtrakuta Empire as one of the four great Empires of the world. The Rashtrakuta period marked the beginning of the golden age of southern Indian mathematics. The great south Indian mathematician

Mahāvīra lived in the Rashtrakuta Empire and his text had a huge impact on the medieval south Indian mathematicians who lived after him.

[204] The Rashtrakuta rulers also patronised men of letters, who wrote in a variety of languages from Sanskrit to the

Apabhraṃśas.

[198]

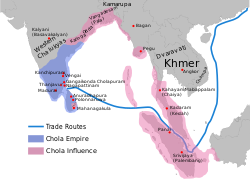

Pala Empire

Nalanda is considered one of the first great universities in recorded history. It was the centre of Buddhist learning and research in the world from 450 to 1193 AD. It reached its height under the Palas.

Landscape of

Vikramashila university ruins, the seating and meditation area. Established by Emperor

Dharmapala.

The

Pala Empire (

Bengali:

পাল সাম্রাজ্য Pal Samrajyô) flourished during the Classical period of India, and may be dated during 750–1174 CE. Founded by

Gopala I,

[205][206][207] it was ruled by a Buddhist dynasty from Bengal in the eastern region of the Indian subcontinent. Though the Palas were followers of the Mahayana and Tantric schools of Buddhism,

[208] they also patronised

Shaivism and

Vaishnavism.

[209] The

morpheme Pala, meaning "protector", was used as an ending for the names of all the Pala monarchs. The empire reached its peak under

Dharmapala and

Devapala. Dharmapala is believed to have conquered Kanauj and extended his sway up to the farthest limits of India in the northwest.

[209] The Pala Empire can be considered as the golden era of Bengal in many ways. Dharmapala founded the

Vikramashilaand revived Nalanda,

[209] considered one of the first great universities in recorded history. Nalanda reached its height under the patronage of the Pala Empire.

[211] The Palas also built many

viharas. They maintained close cultural and commercial ties with countries of Southeast Asia and

Tibet. Sea trade added greatly to the prosperity of the Pala kingdom. The Arab merchant Suleiman notes the enormity of the Pala army in his memoirs.

[209]

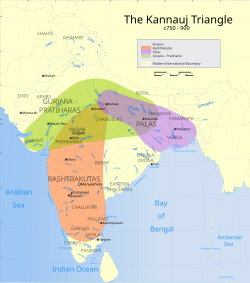

Chola Empire

Medieval Cholas rose to prominence during the middle of the 9th century C.E. and established the greatest empire South India had seen.

[212] They successfully united the South India under their rule and through their naval strength extended their influence in the Southeast Asian countries such as Srivijaya.

[193] Under

Rajaraja Chola I and his successors

Rajendra Chola I,

Rajadhiraja Chola,

Virarajendra Chola and

Kulothunga Chola I the dynasty became a military, economic and cultural power in South Asia and South-East Asia.

[213][214] Rajendra Chola I's navies went even further, occupying the sea coasts from Burma to Vietnam,

[215] the

Andaman and Nicobar Islands, the

Lakshadweep (Laccadive) islands,

Sumatra, and the

Malay Peninsula in Southeast Asia and the Pegu islands. The power of the new empire was proclaimed to the eastern world by the expedition to the

Ganges which Rajendra Chola I undertook and by the occupation of cities of the maritime empire of

Srivijaya in Southeast Asia, as well as by the repeated embassies to China.

[216]

They dominated the political affairs of Sri Lanka for over two centuries through repeated invasions and occupation. They also had continuing trade contacts with the Arabs in the west and with the Chinese empire in the east.

[217] Rajaraja Chola I and his equally distinguished son Rajendra Chola I gave political unity to the whole of Southern India and established the Chola Empire as a respected sea power.

[218] Under the Cholas, the South India reached new heights of excellence in art, religion and literature. In all of these spheres, the Chola period marked the culmination of movements that had begun in an earlier age under the Pallavas. Monumental architecture in the form of majestic temples and sculpture in stone and bronze reached a finesse never before achieved in India.

[219]

Western Chalukya Empire

The

Western Chalukya Empire (

Kannada:

ಪಶ್ಚಿಮ ಚಾಲುಕ್ಯ ಸಾಮ್ರಾಜ್ಯ) ruled most of the

western Deccan,

South India, between the 10th and 12th centuries.

[220] Vast areas between the

Narmada River in the north and

Kaveri River in the south came under Chalukya control.

[220] During this period the other major ruling families of the Deccan, the

Hoysalas, the

Seuna Yadavas of Devagiri, the

Kakatiya dynasty and the Southern

Kalachuri, were subordinates of the Western Chalukyas and gained their independence only when the power of the Chalukya waned during the later half of the 12th century.

[221] The Western Chalukyas developed an architectural style known today as a transitional style, an architectural link between the style of the early Chalukya dynasty and that of the later Hoysala empire. Most of its monuments are in the districts bordering the Tungabhadra River in central Karnataka. Well known examples are the

Kasivisvesvara Temple at

Lakkundi, the

Mallikarjuna Temple at Kuruvatti, the

Kallesvara Temple at Bagali and the

Mahadeva Temple at Itagi.

[222] This was an important period in the development of fine arts in Southern India, especially in literature as the Western Chalukya kings encouraged writers in the native language of

Kannada, and

Sanskrit like the philosopher and statesman

Basava and the great mathematician

Bhāskara II.

[223][224]

Early Islamic intrusions into the Indian subcontinent

The early Islamic literature indicates that the conquest of the Indian subcontinent was one of the very early ambitions of the Muslims, though it was recognised as a particularly difficult one.

[225] After conquering Persia, the Arab

Umayyad Caliphate incorporated parts of what are now Afghanistan and Pakistan around 720.

In 712, Arab Muslim general Muhammad bin Qasim conquered most of the Indus region in modern-day Pakistan for the Umayyad Empire, incorporating it as the "As-Sindh" province with its capital at Al-Mansurah, 72 km (45 mi) north of modern

Hyderabad in Sindh, Pakistan. After several incursions, the Hindu kings east of Indus defeated the Arabs during the

Caliphate campaigns in India, halting their expansion and containing them at Sindh in Pakistan. The south Indian

Chalukya empire under

Vikramaditya II,

Nagabhata I of the

Pratihara dynasty and

Bappa Rawal of the

Guhilot dynasty repulsed the Arab invaders in the early 8th century.

[226]

Several Islamic kingdoms (

sultanates) under both foreign and, newly converted,

Rajput rulers were established across the Northwestern subcontinent (Afghanistan and Pakistan) over a period of a few centuries. From the 10th century, Sindh was ruled by the Rajput

Soomra dynasty, and later, in the mid-13th century by the Rajput

Samma dynasty. Additionally, Muslim trading communities flourished throughout coastal south India, particularly on the western coast where Muslim traders arrived in small numbers, mainly from the Arabian peninsula. This marked the introduction of a third

Abrahamic Middle Eastern religion, following Judaism and Christianity, often in puritanical form.

Mahmud of Ghazni in the early 11th century raided mainly the north-western parts of the Indian sub-continent 17 times, but he did not seek to establish "permanent dominion" in those areas.

[227]

Hindu Shahi

The Kabul Shahi dynasties ruled the

Kabul Valley and

Gandhara (modern-day Pakistan and

Afghanistan) from the decline of the

Kushan Empire in the 3rd century to the early 9th century.

[228]The Shahis are generally split up into two eras: the

Buddhist Shahis and the

Hindu Shahis, with the change-over thought to have occurred sometime around 870. The kingdom was known as the Kabul Shahan or Ratbelshahan from 565-670, when the capitals were located in

Kapisa and Kabul, and later

Udabhandapura, also known as Hund

[229] for its new capital.

[230][231][232]

The Hindu Shahis under

Jayapala, is known for his struggles in defending his kingdom against the

Ghaznavids in the modern-day eastern

Afghanistan and

Pakistan region. Jayapala saw a danger in the consolidation of the Ghaznavids and invaded their capital city of

Ghazni both in the reign of

Sebuktigin and in that of his son

Mahmud, which initiated the

Muslim Ghaznavid and

Hindu Shahi struggles.

[233] Sebuk Tigin, however, defeated him, and he was forced to pay an indemnity.

[233] Jayapala defaulted on the

PAYMENT

and took to the battlefield once more.

[233]Jayapala however, lost control of the entire region between the

Kabul Valley and

Indus River.

[234]

Before his struggle began Jaipal had raised a large army of Punjabi Hindus. When Jaipal went to the

Punjab region, his army was raised to 100,000 horsemen and an innumerable host of foot soldiers. According to

Ferishta:

The two armies having met on the confines of

Lumghan,

Subooktugeen ascended a hill to

VIEW

the forces of Jeipal, which appeared in extent like the boundless ocean, and in number like the ants or the locusts of the wilderness. But Subooktugeen considered himself as a wolf about to attack a flock of sheep: calling, therefore, his chiefs together, he encouraged them to glory, and issued to each his commands. His soldiers, though few in number, were divided into squadrons of five hundred men each, which were directed to attack successively, one particular point of the Hindoo line, so that it might continually have to encounter fresh troops.

[234]

However, the army was hopeless in battle against the western forces, particularly against the young Mahmud of Ghazni.

[234] In the year 1001, soon after Sultan Mahmud came to power and was occupied with the

Qarakhanids north of the

Hindu Kush, Jaipal

attacked Ghazni once more and upon suffering yet another defeat by the powerful Ghaznavid forces, near present-day

Peshawar. After the

Battle of Peshawar, he committed suicide because his subjects thought he had brought disaster and disgrace to the Shahi dynasty.

[233][234]

Jayapala was succeeded by his son

Anandapala,

[233] who along with other succeeding generations of the Shahiya dynasty took part in various unsuccessful campaigns against the advancing Ghaznvids but were unsuccessful. The Hindu rulers eventually exiled themselves to the

Kashmir Siwalik Hills.

[234]

Medieval and Early Modern periods (c. 1206–1858 CE)

The Medieval and Early Modern periods in India is defined by the disruption to native Indian elites by Muslim Central Asian nomadic clans;leading to the

Rajput resistance to Muslim conquests, and growth of Hindu, Muslim, and Sikh, dynasties and empires, built upon new military technology and techniques; the rise of theistic devotional trend of the

Bhakti movement, the cultural synthesis of Hindu and Muslim elements reflected in

Indo-Islamic architecture; and came to an end with the

British Raj.

Growth of Muslim Population in Medieval India

Like other settled, agrarian societies in history, those in the Indian subcontinent have been attacked by nomadic tribes throughout its long history. In evaluating the impact of Islam on the sub-continent, one must note that the northwestern sub-continent was a frequent target of tribes raiding from Central Asia. In that sense, the Muslim intrusions and later Muslim invasions were not dissimilar to those of the earlier invasions during the 1st millennium.

[238] What does however, make the Muslim intrusions and later Muslim invasions different is that unlike the preceding invaders who assimilated into the prevalent social system, the successful Muslim conquerors retained their Islamic identity and created new legal and administrative systems that challenged and usually in many cases superseded the existing systems of social conduct and ethics, even influencing the non-Muslim rivals and common masses to a large extent, though non-Muslim population was left to their own laws and customs. They also introduced new cultural codes that in some ways were very different from the existing cultural codes. This led to the rise of a new Indian culture which was mixed in nature, though different from both the ancient Indian culture and later westernised modern Indian culture. At the same time it must be noted that overwhelming majority of Muslims in India are Indian natives

CONVERTED

to Islam. This factor also played an important role in the synthesis of cultures.

[239]

The growth of Muslim dynasties also caused destruction and desecration of politically important temples of enemy states,

[240] cases of forced conversions to Islam,

[241]PAYMENT of

jizya tax,

[242] and loss of life for the non-Muslim population.

[243] As noted by Historian

Will Durant:

The Mohammedan conquest of India is probably the bloodiest story in history. The Islamic historians and scholars have recorded with great glee and pride the slaughters of Hindus, forced conversions, abduction of Hindu women and children to slave markets and the destruction of temples carried out by the warriors of Islam during 800 AD to 1700 AD. Millions of Hindus were converted to Islam by sword during this period.

[244]

Rajput resistance to Muslim conquests

Before the Muslim expeditions into the Indian subcontinent, much of North and West India were ruled by

Rajput dynasties. The Rajputs were successful in containing Arab Muslim expansion during the

Caliphate campaigns in India; but, later Central Asian Muslim Turks were able to break through the Rajput defence into the Indian heartland. However, the Rajputs held out against the Muslim Turkic empires for several centuries. They earned a reputation by fighting battles with code of chivalrous conduct rooted in a strong adherence to tradition and Chi.

[245]

- The Rajput Chauhan dynasty established rule over Delhi and Ajmer in the 10th century. The most popular ruler of this dynasty was Prithviraj Chauhan. His reign marked one of the most significant moment in Indian history; his battles with Muslim Sultan Muhammad Ghori. The First Battle of Tarain, Ghori was defeated with heavy losses. However, the Second Battle of Tarain saw the Rajput army eventually defeated, laying the foundation of Muslim rule in mainland India.[246]

- Mewar dynasty under Maharana Hammir defeated Muhammad Tughlaq with Bargujars as his main allies, and captured him. Tughlaq had to pay a huge ransom and relinquish all of Mewar's lands. After this event, the Delhi Sultanate did not attack Chittorgarh for a few hundred years. The Rajputs reestablished their independence, and Rajput states were established as far east as Bengal and north into the Punjab. The Tomaras established themselves at Gwalior, and the ruler Man Singh Tomar built the fortress which still stands there.[247]

- Mewar emerged as the leading Rajput state, and Rana Kumbha expanded his kingdom at the expense of the sultanates of Malwa and Gujarat.[247][248]

- Rana Sanga of Mewar became the principal player in Northern India. His objectives grew in scope – he planned to conquer the much sought after prize of the Muslim rulers of the time, Delhi. However, his defeat in the Battle of Khanwa consolidated the new Mughal dynasty in India.[247]

- Maharana Pratap of Mewar, a 16th-century Rajput ruler firmly resisted the Mughals. Akbar sent many missions against him. He survived to ultimately gain control of all of Mewar, excluding Chittorgarh Fort.[249]

- The Chittorgarh Fort is the largest in India; it is a symbol for Rajput resistance. Chittorgarh Fort was sacked three times between the 15th and 16th centuries by Muslim armies; in 1303 Allauddin Khilji defeated Rana Ratan Singh; in 1535 Bahadur Shah, the Sultanate of Gujarat defeated Bikramjeet Singh; and in 1567 Akbar defeated Maharana Udai Singh II, who left the fort and founded Udaipur. Each time the men fought bravely rushing out of the fort walls charging the enemy, but lost. Following these defeats, Jauhar was committed thrice by more than 13,000 ladies and children of the Rajput soldiers who laid their lives in battles at Chittorgarh Fort; first led by Rani Padmini wife of Rana Rattan Singh who was killed in the battle in 1303, and later by Rani Karnavati in 1537 AD.[250][251][252]

Delhi Sultanate

In the 12th and 13th centuries, Central Asian

Turks invaded parts of northern India and established the

Delhi Sultanate in the former Hindu holdings.

[253]

Historian Dr. R.P. Tripathi noted:

The history of Muslim sovereignty in India begins properly speaking with

Iltutmish.

[254]

The subsequent

Slave dynasty of

Delhi managed to conquer large areas of northern India, while the

Khilji dynasty conquered most of central India but were ultimately unsuccessful in conquering and uniting the subcontinent. The Sultanate ushered in a period of Indian cultural renaissance. The resulting "Indo-Muslim" fusion of cultures left lasting syncretic monuments in architecture, music, literature, religion, and clothing. It is surmised that the language of

Urdu (literally meaning "horde" or "camp" in various Turkic dialects) was born during the Delhi Sultanate period as a result of the intermingling of the local speakers of Sanskritic

Prakrits with immigrants speaking

Persian,

Turkic, and

Arabic under the Muslim rulers. The Delhi Sultanate is the only Indo-Islamic empire to enthrone one of the few female rulers in India,

Razia Sultana (1236–1240).

A

Turco-Mongol conqueror in Central Asia,

Timur (Tamerlane), attacked the reigning Sultan Nasir-u Din Mehmud of the

Tughlaq Dynasty in the north Indian city of Delhi.

[255] The Sultan's army was defeated on 17 December 1398. Timur entered Delhi and the city was sacked, destroyed, and left in ruins, after Timur's army had killed and plundered for three days and nights. He ordered the whole city to be sacked except for the

sayyids, scholars, and the "other Muslims" (artists); 100,000 war prisoners were put to death in one day.

[256] The Sultanate suffered significantly from the sacking of Delhi revived briefly under the Lodi Dynasty, but it was a shadow of the former.

Bhakti movement and Sikhism

The

Bhakti movement refers to the

theistic devotional trend that emerged in medieval

Hinduism and later revolutionised in

Sikhism.

[259] It originated in the seventh-century south India (now parts of Tamil Nadu and Kerala), and spread northwards. It swept over east and north India from the 15th century onwards, reaching its zenith between the 15th and 17th century CE.

- The Bhakti movement regionally developed around different gods and goddesses, such as Vaishnavism (Vishnu), Shaivism (Shiva), Shaktism (Shakti goddesses), andSmartism.[261][262][263] The movement was inspired by many poet-saints, who championed a wide range of philosophical positions ranging from theistic dualism of Dvaita to absolute monism of Advaita Vedanta.[265]

- Sikhism is based on the spiritual teachings of Guru Nanak, the first Guru,[266] and the ten successive Sikh gurus. After the death of the tenth Guru, Guru Gobind Singh, the Sikh scripture, Guru Granth Sahib, became the literal embodiment of the eternal, impersonal Guru, where the scripture's word serves as the spiritual guide for Sikhs.[267][268][269]

Vijayanagara Empire

The Vijayanagara Empire was established in 1336 by Harihara I and his brother Bukka Raya I of Sangama Dynasty.

[270] The empire rose to prominence as a culmination of attempts by the southern powers to ward off Islamic invasions by the end of the 13th century.

[271] The empire is named after its capital city of Vijayanagara, whose ruins surround present day Hampi, now a World Heritage Site in Karnataka, India.

[272]

The empire's legacy includes many monuments spread over South India, the best known of which is the group at Hampi. The previous temple building traditions in South India came together in the Vijayanagara Architecture style. The mingling of all faiths and vernaculars inspired architectural innovation of Hindu temple construction, first in the Deccan and later in the Dravidian idioms using the local granite. South Indian mathematics flourished under the protection of the Vijayanagara Empire in Kerala. The south Indian mathematician

Madhava of Sangamagrama founded the famous

Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics in the 14th century which produced a lot of great south Indian mathematicians like

Parameshvara,

Nilakantha Somayaji and

Jyeṣṭhadeva in medieval south India.

[273] Efficient administration and vigorous overseas trade brought new technologies such as water management systems for irrigation.

[274] The empire's patronage enabled fine arts and literature to reach new heights in Kannada, Telugu, Tamil and Sanskrit, while Carnatic music evolved into its current form.

[275]

The Vijayanagara Empire created an epoch in South Indian history that transcended regionalism by promoting Hinduism as a unifying factor. The empire reached its peak during the rule of

Sri Krishnadevaraya when Vijayanagara armies were consistently victorious. The empire annexed areas formerly under the Sultanates in the northern Deccan and the territories in the eastern Deccan, including Kalinga, while simultaneously maintaining control over all its subordinates in the south.

[276] Many important monuments were either completed or commissioned during the time of Krishna Deva Raya. Vijayanagara went into decline after the defeat in the

Battle of Talikota (1565).

Regional powers

For two and a half centuries from the mid 13th, the politics in the Northern India was dominated by the

Delhi Sultanate and in the Southern India by the

Vijayanagar Empire which originated as a political heir of the erstwhile

Hoysala Empire and

Pandyan Empire.

[277] However, there were other regional powers present as well. In the North, the

Rajputs were a dominant force in the Western and Central India. Their power reached to the zenith under

Rana Sanga during whose time Rajput armies were constantly victorious against the Sultanate army.

[278] In the South, the

Bahmani Sultanate was the chief rival of the Vijaynagara and gave Vijayanagara tough days many a times.

[279] In the early 16th century

Krishnadevaraya of the Vijayanagara Empire defeated the last remnant of Bahmani Sultanate power after which the Bahmani Sultanate collapsed.

[280] It was established either by a Brahman convert or patronised by a Brahman and form that source it got the name

Bahmani.

[281] In the early 16th century, it collapsed and got split into five small

Deccan sultanates.

[282] In the East, the

Gajapati Kingdom remained a strong regional power to reckon with.

[283] In the Northeast the

Ahom Kingdom was a major power for six centuries;

[284][285] and the

Kingdom of Manipur, which ruled from their seat of power at

Kangla Fort and developed a sophisticated Hindu

Gaudiya Vaishnavite culture.

[286]

Mughal Empire

In 1526,

Babur, a

Timurid descendant of

Timur and

Genghis Khan from

Fergana Valley (modern day Uzbekistan), swept across the

Khyber Pass and established the

Mughal Empire, which at its zenith covered modern day Afghanistan, Pakistan, India and Bangladesh.

[289]However, his son

Humayun was defeated by the Afghan warrior

Sher Shah Suri in the year 1540, and Humayun was forced to retreat to

Kabul. After Sher Shah's death, his son

Islam Shah Suri and the Hindu emperor

Hemu Vikramaditya, who had won 22 battles against Afghan rebels and forces of Akbar, from

Punjab to

Bengal and had established a secular rule in North India from

Delhi till 1556 after winning

Battle of Delhi.

Akbar's forces defeated and killed Hemu in the

Second Battle of Panipat on 6 November 1556.

Akbar's son,

Jahangir more or less followed father's policy. The Mughal dynasty ruled most of the Indian subcontinent by 1600. The reign of

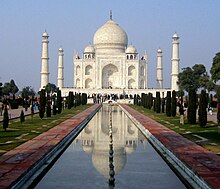

Shah Jahan was the golden age of Mughal architecture. He erected several large monuments, the most famous of which is the

Taj Mahal at Agra, as well as the Moti Masjid, Agra, the Red Fort, the

Jama Masjid, Delhi, and the Lahore Fort. The Mughal Empire reached the zenith of its territorial expanse during the reign of

Aurangzeb and also started its terminal decline in his reign due to Maratha military resurgence under

Shivaji. Historian

Sir. J.N. Sarkar wrote, "All seemed to have been gained by Aurangzeb now, but in reality all was lost."

[290] The same was echoed by

Vincent Smith: "The Deccan proved to be the graveyard not only of Aurangzeb's body but also of his empire".

[143]

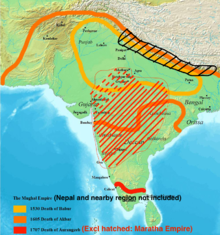

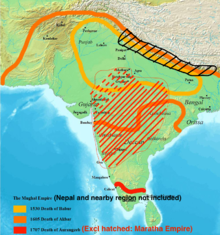

Expansion of the Mughal Empire from 1526 to 1700.

The empire went into decline thereafter. The Mughals suffered several blows due to invasions from

Marathas and

Afghans. During the decline of the Mughal Empire, several smaller states rose to fill the power vacuum and themselves were contributing factors to the decline. In 1737, the Maratha general

Bajirao of the Maratha Empire invaded and plundered Delhi. Under the general Amir Khan Umrao Al Udat, the Mughal Emperor sent 8,000 troops to drive away the 5,000 Maratha cavalry soldiers. Baji Rao, however, easily routed the novice Mughal general and the rest of the imperial Mughal army fled. In 1737, in the final defeat of Mughal Empire, the commander-in-chief of the Mughal Army, Nizam-ul-mulk, was routed at Bhopal by the Maratha army. This essentially brought an end to the Mughal Empire. In 1739,

Nader Shah, emperor of Iran, defeated the Mughal army at the

Battle of Karnal.

[291] After this victory, Nader captured and sacked Delhi, carrying away many treasures, including the

Peacock Throne.

[292] The

Mughal dynasty was reduced to puppet rulers by 1757. The remnants of the Mughal dynasty were finally defeated during the

Indian Rebellion of 1857, also called the 1857 War of Independence, and the remains of the empire were formally taken over by the British while the

Government of India Act 1858 let the

British Crown assume direct control of India in the form of the new

British Raj.

The Mughals were perhaps the richest single dynasty to have ever existed. During the Mughal era, the dominant political forces consisted of the Mughal Empire and its tributaries and, later on, the rising successor states – including the Maratha Empire – which fought an increasingly weak Mughal dynasty. The Mughals, while often employing brutal tactics to subjugate their empire, had a policy of integration with Indian culture, which is what made them successful where the short-lived Sultanates of Delhi had failed. This period marked vast social change in the subcontinent as the Hindu majority were ruled over by the Mughal emperors, most of whom showed religious tolerance, liberally patronising Hindu culture. The famous emperor Akbar, who was the grandson of Babar, tried to establish a good relationship with the Hindus. However, later emperors such as

Aurangazeb tried to establish complete Muslim dominance, and as a result several historical temples were destroyed during this period and taxes imposed on non-Muslims. Akbar declared "Amari" or non-killing of animals in the holy days of Jainism. He rolled back the

jizya tax for non-Muslims. The Mughal emperors married local royalty, allied themselves with local

maharajas, and attempted to fuse their Turko-Persian culture with ancient Indian styles, creating a unique

Indo-Saracenic architecture. It was the erosion of this tradition coupled with increased brutality and centralisation that played a large part in the dynasty's downfall after Aurangzeb, who unlike previous emperors, imposed relatively non-pluralistic policies on the general population, which often inflamed the majority Hindu population.

Maratha Empire

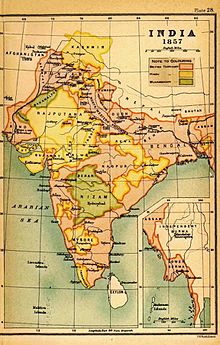

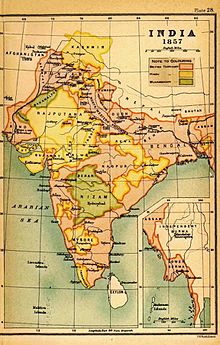

Political map of Indian Subcontinent in 1758. The

Maratha Empire (orange)was the last Hindu empire of India.

Shaniwarwada palace fort in

Pune, it was the seat of the Peshwa rulers of the Maratha Empire until 1818.

The early 18th century saw the rise of Maratha suzerainty over the Indian Subcontinent. Under the Peshwas, the

Maratha Empire consolidated and ruled over much of the Subcontinent. The

Marathas are credited to a large extent for ending the

Mughal rule in India.

[293][294][295]

Historian K.K. Datta wrote about Bajirao I:

He may very well be regarded as the second founder of the Maratha Empire.

[297]

By the early 18th century, the Maratha Kingdom had transformed itself into the Maratha Empire under the rule of the

Peshwas (prime ministers). In 1737, the Marathas defeated a Mughal army in their capital, Delhi itself in

Battle of Delhi (1737). The Marathas continued

their military campaigns against

Mughals,

Nizam,

Nawab of Bengal and Durrani Empire to further extend their boundaries.

Gordon explained how the Maratha systematically took control over new regions. They would start with annual raids, followed by collecting ransom from villages and towns while the declining Mughal Empire retained nominal control and finally taking over the region. He explained it with the example of Malwa region. Marathas built an efficient system of public administration known for its attention to detail. It succeeded in raising revenue in districts that recovered from years of raids, up to levels previously enjoyed by the Mughals. For example, the cornerstone of the Maratha rule in Malwa rested on the 60 or so local tax collectors who advanced the Maratha ruler

Peshwa a portion of their district revenues at interest.

[298] By 1760, the domain of the Marathas stretched across practically the entire subcontinent.

[299]

India contains no more than two great powers, British and Mahratta, and every other state acknowledges the influence of one or the other. Every inch that we recede will be occupied by them.

[302][303]

The Marathas also developed a potent

navy circa 1660s, which at its peak, dominated the territorial waters of the western coast of India from

Mumbai to

Savantwadi.

[304] For a brief period, the Maratha Navy also established its base at the

Andaman Islands in the

Bay of Bengal.

[305] It would engage in attacking the

British,

Portuguese,

Dutch, and

SiddiNaval ships and kept a check on their naval ambitions. The Maratha Navy dominated till around the 1730s, was in a state of decline by the 1770s, and ceased to exist by 1818.

[306]

Sikh Empire

Harmandir Sahib or

The Golden Temple is culturally the most significant place of worship for the

Sikhs.

Maharaja Ranjit Singh consolidated many parts of northern India into an empire. He primarily used his highly disciplined

Sikh Khalsa Army that he trained and equipped with modern military technologies and technique. Ranjit Singh proved himself to be a master strategist and selected well qualified generals for his army. He continuously defeated the Afghan armies and successfully ended the

Afghan-Sikh Wars. In stages, he added the central Punjab, the provinces of Multan and Kashmir, the Peshawar Valley, and the Derajat to his empire.

[307][308]

At its peak, in the 19th century, the empire extended from the

Khyber Pass in the west, to

Kashmir in the north, to

Sindh in the south, running along Sutlej river to

Himachal in the east. After the death of Ranjit Singh, the empire weakened, leading to the conflict with the British East India Company. The hard-fought

first Anglo-Sikh war and

second Anglo-Sikh war marked the downfall of the Sikh Empire; making it among the last areas of the Indian subcontinent to be conquered by the British.

Other kingdoms

There were several other kingdoms which ruled over parts of India in the later medieval period prior to the British occupation. However, most of them were bound to pay regular tribute to the

Marathas.

[299] The rule of

Wodeyar dynasty which established the

Kingdom of Mysore in southern India in around 1400 CE by was interrupted by

Hyder Ali and his son

Tipu Sultan in the later half of the 18th century. Under their rule, Mysore fought a

series of wars sometimes against the combined forces of the British and

Marathas, but mostly against the British, with Mysore receiving some aid or promise of aid from the French.

The

Nawabs of Bengal had become the de facto rulers of

Bengal following the decline of Mughal Empire. However, their rule was interrupted by Marathas who carried

six expeditions in Bengal from 1741 to 1748 as a result of which Bengal became a tributary state of Marathas.

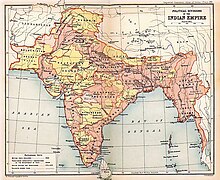

The 18th century saw the whole of